Il riscatto come speranza

di Roberto Mutti

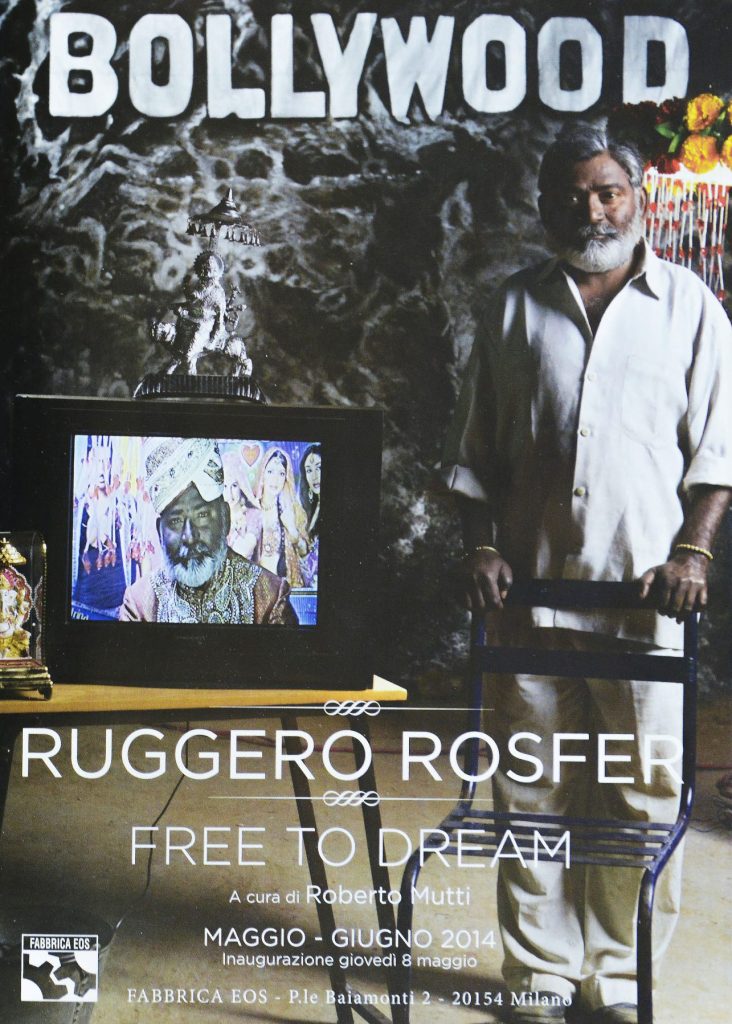

Facciamoci caso: nei racconti, nelle leggende, nei miti e nelle favole ai protagonisti viene spesso chiesto di esprimere un desiderio. La domanda viene quasi sempre posta alle persone semplici che si riveleranno capaci di risposte equilibrate e intelligenti al contrario di quanto succede a ricchi o potenti che, nelle rare volte in cui sono chiamati in causa, dimostreranno la loro goffa inadeguatezza. Se in questa dimensione favolistica gli umili hanno come premio la possibilità di sorprendenti scalate sociali e i poveri quella di accedere improvvisamente alla ricchezza, che cosa succede nella dura realtà quotidiana così lontana dalle edulcorate fantasie nate per regalare almeno la via di fuga della consolazione? Ruggero Rosfer, postosi la domanda, ha realizzato un progetto molto articolato nel suo essere nel contempo realistico e immaginifico perché va a cogliere una contraddizione di fondo del mondo contemporaneo, quella che contrappone essere ed apparire e che la fotografia, per la sua stessa essenza, tende a far emergere. Anche in questo caso i protagonisti sono quanti non detengono altro potere che la loro immaginazione, sono gli ultimi, i diseredati o meglio dire, visto che ci troviamo in India, gli appartenenti alla casta degli intoccabili. Siamo nella città di Jaipur in Rajasthan ed è qui – in una zona dove le baracche che fungono da abitazioni non hanno corrente elettrica né servizi né acqua corrente – che l’equipe di Rosfer ha dato vita a “Liberi di sognare”, progetto che vede ugualmente coinvolti pittura, video e fotografia. Tutto è stato giocato sulle contraddizioni già a cominciare dal prezioso dipinto realizzato dallo scenografo Marzio Cardaropoli dove, sulla riproduzione della collina che sovrasta Los Angeles la scritta Bollywood sostituisce l’originale Hollywood. Posizionato fra le baracche, fa da fondale al set fotografico dove Ruggero Rosfer ha fatto posare uomini, donne, ragazzi accanto al televisore dove passavano le immagini dei video precedentemente realizzati dall’autrice e regista Monica Onore riprendendo loro stessi vestiti come fossero i divi cinematografici dei poster appesi alle loro spalle. Colpisce il contrasto fra l’eleganza del travestimento e l’essenzialità degli abiti di tutti i giorni ma è negli sguardi ugualmente intensi, nelle posture sempre dignitose che si coglie la loro volontà di coniugare la realtà e il sogno o, come si diceva un tempo, il pane e le rose. Il fotografo usa tutta la sua perizia per isolare i soggetti che emergono dal buio dello sfondo per comparire come fossero su un palco teatrale dove però recitano la loro stessa vita con una spontaneità toccante. Ma davvero costoro vogliono vivere in una favola? Ancora una volta la realtà si fa sentire ed è insieme forte e poetica, aspra e struggente: la si legge nelle risposte date ai questionari sottoposti ai soggetti. Tornano ancora una volta i desideri e alla domanda su che sogni coltivano, nessuno parla più del cinema. La ragazzina che pascola le capre vorrebbe sposarsi, la casalinga far studiare la figlia, il giovane meccanico possedere una nuova bicicletta, una donna diventare una brava moglie, un uomo possedere una casa. Ora è inevitabile tornare a osservare i ritratti, per cogliere in quegli sguardi miti il desiderio forte di un riscatto che forse la realtà non concederà agli intoccabili anche se la fotografia, per un attimo, può farlo immaginare.

Redemption out of hope

by Roberto Mutti

You may have noticed that in stories, legends, myths and fairy tales the protagonists are often asked to make a wish. Nearly always, the question is posed to an ordinary person who proves capable of intelligent and balanced responses, in contrast to what happens to the rich and powerful, who, when occasionally prompted to respond, only demonstrate their inadequacies. If in this fablelike dimension the humbles are rewarded with the possibility of amazing social climbing, and the poor gain sudden access to wealth, what happens in the harsh reality of everyday life, so distant from these sweetened fantasies created to offer an escape route from reality? Ruggero Rosfer asked himself the question, creating a project so articulate to be both realistic and imaginative at the same time because it grasps a basic contradiction of the contemporary world, that between being and appearing, which photography, by its very essence, is able to expose. Also in this case the protagonists are those who hold no other power than their imagination, they are the last, the underprivileged, or rather, since we are in India, the untouchables. It is here, in the city of Jaipur in Rajasthan – an area where shacks serve as homes without electricity, toilets or running water – that Rosfer’s team gave birth to “Free to dream”, a project which involves painting, video and photography in equal parts. The exhibition plays on contradictions beginning with the precious painting created by set designer Marzio Cardaropoli: a reproduction of the hill overlooking Los Angeles where the original sign Hollywood has been replaced with the sign Bollywood. Located amongst the shacks, the painting is the backdrop of the photographic set. Ruggero Rosfer positioned men, women and children next to a TV screen featuring images from videos previously made by author and director Monica Onore, who filmed them dressed up as if they were the stars of the movie posters on the wall behind them. The contrast between the formality of the elegant clothes and the simplicity of the everyday clothes is striking, but it is in the gaze, equally intense, and the always dignified postures that their desire to combine reality and dream, or as we used to say, bread and roses, is captured. The photographer used all his artistry to isolate the subjects, who emerge from the darkness of the background to appear as if they were on a theatrical stage. Once upon the stage, however, it is their own life that plays out with touching spontaneity. Do they really want to live in a fairy tale? Once again, reality leaves its mark and is both strong and poetic, harsh and moving, as we can see from the responses to the questionnaires submitted to the subjects. Wishes come back once again, however the answer to the question “which dreams to nurture”, is no longer cinema. The young girl goatherd would like to marry, the housewife to give her daughter an education, the young mechanic to buy a new bicycle, a woman to become a good wife, a man to own a house. Now it is inevitable, when looking back at the portraits, to seize in those gentle eyes the strong desire for redemption that reality does not allow to the untouchables, even though photography may makes us imagine so, if only for a moment.